Această recenzie poate conține spoilere

"Tragedy in life starts with the bondage of parent and child"

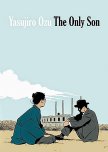

The Only Son is considered director Ozu's first talkie. Even with the spoken dialogue he still leaves space and silence to contemplate his characters' actions and conflicts. Classically Ozu, he studies the relationship between a parent and grown child. Instead of the wealthier families of some of his later films, this widow and child are living in poverty. In this film he also has the son and mother begin to define what success means to them and the emotional cost of failure.

The story begins in 1923 in rural Japan. The mother works at a silk factory doing rigorous physical labor. Her son wants to continue his education, an education she can't afford. His teacher who is preparing to leave for Tokyo stops by the house congratulating the surprised mother on allowing him to go to high school as the son had told him she'd agreed to it. Ultimately, she decides to make whatever sacrifices she must for him to have a better chance in life. The last thing he tells her is that he will become a great man.

The story jumps ahead to 1935 with the mother missing her son and deciding to go visit him in Tokyo. Mother and son have not seen each other in years and seem happy to be together again. The son has a surprise for his mother, he is married and has an infant son. He also is working as a night school geometry teacher and living in a small house in view of the garbage incinerator smokestacks. This brings about the critical theme of the film. The son is ashamed of his job and lifestyle after the sacrifices his mother made for him. The mother is disappointed that he seems to have given up on attaining a better life. Much like in Tokyo Chorus, 1930's Tokyo is portrayed as the great dream destroyer.

Later in the film, the son helps a neighbor in such a way, that the mother beams at him with pride. He may not have become the great man she'd hoped for, but he had become a good man with a good wife. For her, this is enough to ease her worries about him. This is success in her eyes.

Ozu uses many of the techniques and compositions that will define his later work. Filming from the mat, even when in a car is in place. His ubiquitous teapot takes center stage in many scenes. As always, every prop, every angle is thoughtfully and creatively brought together to be aesthetically pleasing and to help tell the story. At one point after an emotional confrontation between mother and son, with his wife sobbing in the background, Ozu lingers on a shot of a painting on a wall near a window and holds that shot for almost a minute, as night turns to day. Almost as if the raw emotions of his characters needed time to be processed by them and us.

Tokyo was the great soul crusher, and during this time the depression had finally caught up with Japan, making work hard to come by. The son's teacher had to become a cook in a small restaurant. The teacher was played by Ozu regular Ryu Chishu, someone you could always count on to bring a character quietly to life. Lida Choko conveyed the mother longing to see her son, happy to be in his presence, and also discouraged at his negative resolution perfectly. Himori Shinichi felt like the weaker acting link. He spent much of his time smiling and gave no inkling of his character's desperate emotions for most of the film.

Interestingly Ozu had the mother and son go to the movies and watch a popular German talkie. Rather lengthy clips of the film were shown. The son's house also had some posters from German movies. Though imminently Japanese, the great director was also open to influence from foreign films.

The German film was one of the only outings we see that the son took his mother on as he spent most of their money trying to show her Tokyo. Unlike so many of the ungrateful male characters in older movies, ones women sacrificed everything for, this son, despite the financial hardship, wants his mother to have a special time. He wants to make her sacrifice worthwhile and up until then had felt he'd completely failed. Even with hardships, disappointments, and setbacks, the film had a warmth and gentle humanity to it. Life wasn't easy, but the film showed the value of family and friendship, of looking out for each other.

As so often happens in Ozu's films, the parent ends up alone. The mother may have been alone, but after seeing the man her son had become could find acceptance in her trials and life. The son, reinvigorated from his mother's belief in him, sat aside his nihilistic acceptance to once again hope. This quiet film was realistic and engaging on many levels. Easily one of my favorite Ozu films.

10/24/22

The story begins in 1923 in rural Japan. The mother works at a silk factory doing rigorous physical labor. Her son wants to continue his education, an education she can't afford. His teacher who is preparing to leave for Tokyo stops by the house congratulating the surprised mother on allowing him to go to high school as the son had told him she'd agreed to it. Ultimately, she decides to make whatever sacrifices she must for him to have a better chance in life. The last thing he tells her is that he will become a great man.

The story jumps ahead to 1935 with the mother missing her son and deciding to go visit him in Tokyo. Mother and son have not seen each other in years and seem happy to be together again. The son has a surprise for his mother, he is married and has an infant son. He also is working as a night school geometry teacher and living in a small house in view of the garbage incinerator smokestacks. This brings about the critical theme of the film. The son is ashamed of his job and lifestyle after the sacrifices his mother made for him. The mother is disappointed that he seems to have given up on attaining a better life. Much like in Tokyo Chorus, 1930's Tokyo is portrayed as the great dream destroyer.

Later in the film, the son helps a neighbor in such a way, that the mother beams at him with pride. He may not have become the great man she'd hoped for, but he had become a good man with a good wife. For her, this is enough to ease her worries about him. This is success in her eyes.

Ozu uses many of the techniques and compositions that will define his later work. Filming from the mat, even when in a car is in place. His ubiquitous teapot takes center stage in many scenes. As always, every prop, every angle is thoughtfully and creatively brought together to be aesthetically pleasing and to help tell the story. At one point after an emotional confrontation between mother and son, with his wife sobbing in the background, Ozu lingers on a shot of a painting on a wall near a window and holds that shot for almost a minute, as night turns to day. Almost as if the raw emotions of his characters needed time to be processed by them and us.

Tokyo was the great soul crusher, and during this time the depression had finally caught up with Japan, making work hard to come by. The son's teacher had to become a cook in a small restaurant. The teacher was played by Ozu regular Ryu Chishu, someone you could always count on to bring a character quietly to life. Lida Choko conveyed the mother longing to see her son, happy to be in his presence, and also discouraged at his negative resolution perfectly. Himori Shinichi felt like the weaker acting link. He spent much of his time smiling and gave no inkling of his character's desperate emotions for most of the film.

Interestingly Ozu had the mother and son go to the movies and watch a popular German talkie. Rather lengthy clips of the film were shown. The son's house also had some posters from German movies. Though imminently Japanese, the great director was also open to influence from foreign films.

The German film was one of the only outings we see that the son took his mother on as he spent most of their money trying to show her Tokyo. Unlike so many of the ungrateful male characters in older movies, ones women sacrificed everything for, this son, despite the financial hardship, wants his mother to have a special time. He wants to make her sacrifice worthwhile and up until then had felt he'd completely failed. Even with hardships, disappointments, and setbacks, the film had a warmth and gentle humanity to it. Life wasn't easy, but the film showed the value of family and friendship, of looking out for each other.

As so often happens in Ozu's films, the parent ends up alone. The mother may have been alone, but after seeing the man her son had become could find acceptance in her trials and life. The son, reinvigorated from his mother's belief in him, sat aside his nihilistic acceptance to once again hope. This quiet film was realistic and engaging on many levels. Easily one of my favorite Ozu films.

10/24/22

Considerați utilă această recenzie?

55

55 223

223 11

11