Cat-Loving Haruki Murakami and the Abundance of Movie Adaptations

Cat-Loving Haruki Murakami and the Abundance of Movie Adaptations

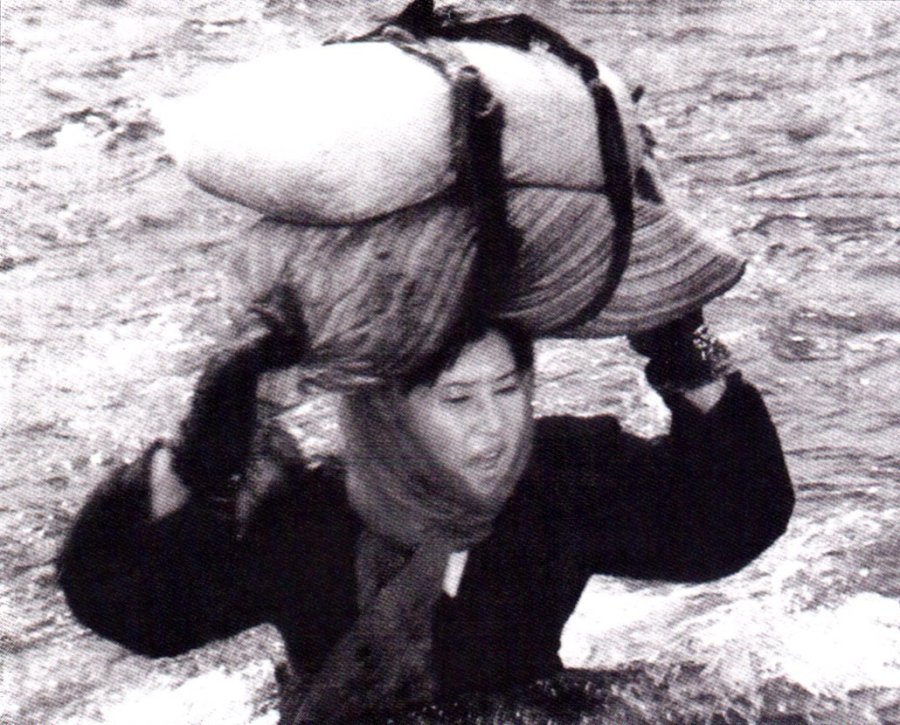

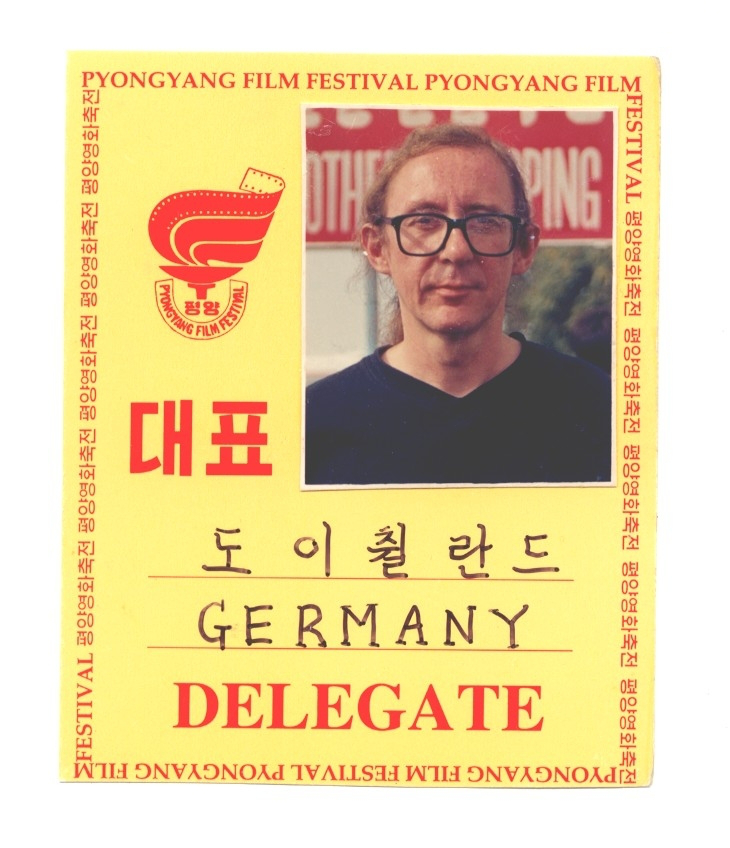

Johannes Schönherr with Pulgasari actress Jang Son Hui in Pyongyang, 2000.

Johannes Schönherr with Pulgasari actress Jang Son Hui in Pyongyang, 2000.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this interview are solely those of the interviewee and do not necessarily represent the views of MyDramaList or its writers.

“Cinema occupies an important place in the overall development of art and literature. As such, it is a powerful ideological weapon for the revolution and construction.” (Kim Jong Il)

Over a year ago, MDL users had a chance to learn a bit about the wonders of North Korean cinema and dramas in our article titled From Best Korea with Love: An Introduction to North Korean Dramas and Movies. This time, we present you an exclusive interview with an expert on the DPRK filmography, Johannes Schönherr. Mr Schönherr majored in Cinema Studies at New York University. Apart from having authored numerous academic and online articles, he writes about his visits to Pyongyang in his book Trashfilm Roadshows, and wrote the first-ever book on the history of North Korean cinema, North Korean Cinema – A History. He currently resides in Japan.

- Why North Korean cinema? What made you interested in movies from the Hermit Kingdom?

It’s a long story but I will try to keep it short. I’ve always been interested in strange and bizarre movies – and in the places those movies came from. In the early 1990s, my focus was on the American underground, especially the Cinema of Transgression. I organized European tours for some of those underground filmmakers and eventually moved to New York myself. There, I met a Japanese girl who organized a Japan tour for me, screening a program of American punk porn shorts. That was in 1997. At the same time, the Filmhuset (Film House) in Copenhagen asked me to curate a package of about 10 Japanese underground/cyberpunk movies to screen in Europe. I did that and it went well.

So, after American punk porn and Japanese cyberpunk, where do you go next? I had read that North Korea produces movies and exploring those seemed like an adventure. I mentioned that idea to a friend who ran a small independent movie house in Berlin. He just said: “You want to meet North Korean film people? Diplomats of the North Korean embassy come to our office every week asking us to find film prints for them. Probably for the viewing pleasure of their Great Leader. I can tell them about your idea.”

The original logo of Chosun Film Company. | About a week later, during the Berlin Film Festival in February 1999, I got a call from my friend, telling me: “I told the North Koreans about you. They have a high level movie delegation here right now. They want to meet you. Get to Berlin quickly.” So, I went to Berlin and met the vice president of the Korea Film Import & Export Corporation. He liked my idea of touring a program of North Korean features around Europe. I made one condition, though: I would have to visit North Korea before I tour any of their films. |

On the invitation of this vice president of the Korea film export company, I went to Pyongyang in September 1999. I stayed there for about 10 days and got private screenings in the cute little private theater the film export corp. operated. From the films I watched there, all on the professional 35mm format, I made my selection. Some pretty cool martial arts movies, some social realist pictures, some over-the-top propaganda.

In Spring 2000, I toured that package of North Korean films through Europe.

After that, I kept up my interest in North Korean cinema, did more research and eventually wrote my book North Korean Cinema – A History.

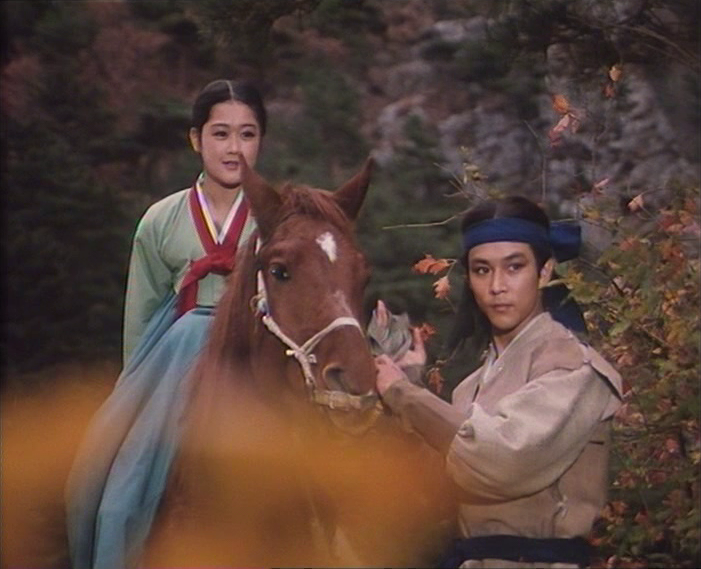

Shooting of Pulgasari (1985) at Korean Film Studio, Pyongyang.

- Obviously, North Korean movies serve propaganda purposes; however, regardless of the appraisal of the Kim regime, can they be enjoyed for what they are? Can you provide some examples?

North Korea produced some pretty good martial arts films, like Hong Kil Dong, to give an example of a movie set in medieval times or the really stunning Order No. 027, set in the Korean War. Then of course, there is Pulgasari, the North Korean Godzilla movie, employing a lot of actual Godzilla staff from the Toho Studios in Tokyo, including Kenpachiro Satsuma inside the Pulgasari rubber suit. Satsuma was the man inside the Godzilla rubber suit at the time (1980s).

On the other hand, if you are interested in North Korean society, there is a lot to discover in modern social realist dramas like, say, Our Fragrance (2004). That’s quite an enjoyable light romantic comedy.

Sure, there are a lot of films with heavy political messages but there are also quite a lot of movies that can be enjoyed simply as movies.

- Do you have any all-time favourite DPRK productions?

Aside from the ones mentioned above, that would certainly be Runaway (1984) and Salt (1985), both directed by Shin Sang Ok and starring his wife, Choi Un Hee. Though those films feature at the end the usual praise of Great Leader Kim Il Sung, they are cinematic masterpieces. Really gripping, full of drama and masterly shot.

Shin was a South Korean director and Choi a South Korean movie star. Kim Jong Il “enlisted” them to upgrade the quality of North Korean films. In 1986, they both made a run in Vienna and successfully escaped the grip of their dictatorial producer.

Choi Un Hee in Salt (1985). |  Jang Son Hui in Hong Kil Dong (1986). |

- We are aware of the fact that you were in Pyongyang. Did you manage to visit Korean Film Studio or maybe attend a film festival organised by the authorities?

Yes, I attended the Pyongyang International Film Festival in September 2000. For the festival guests, a visit to the Korean Film Studio was part of the official program. What I liked the best about the visit there was being able to meet some of the actresses in my favorite North Korean movies at an officially arranged event. Like, for example, Jang Son Hui, the main actress of Pulgasari.

- Many sources emphasise that Kim Jong Il was a massive movie buff. How do you perceive the state of DPRK filmmaking under the rule of Kim Jong Un?

Kim Jong Un didn’t inherit the movie gene from his father, it seems. His focus seems to be on entertainment parks and perhaps pop music.

Therefore, hardly any new movies seem to get produced in North Korea. But then, like in the rest of the world, the general focus seems to shift towards TV dramas in North Korea as well.

I used to get the calendars published by the Korea Film Import & Export Corporation. Ten years ago, there was an image of a movie star or a film still from a major production on every monthly page.

Recently, more than half of the pages feature stills from TV dramas.

A selection of North Korean titles officially issued by the government.

A selection of North Korean titles officially issued by the government.

- Nowadays, many DPRK films are accessible online. How did you manage to conduct research on North Korean films in the pre-Youtube era?

Of course, I saw a lot of movies while visiting North Korea in 1999 and 2000.

For a more thorough research, I went to north-east China. There, they got huge Koreatowns, like Xita in the city of Shenyang. All kinds of Koreans live there, Chinese Koreans, North Koreans, South Koreans, American Koreans and so on. There, they got video stores selling both South and North Korean films on DVD or, more often in the case of the North Korean ones, VCD – Video Compact Disks.

Also, there are many North Korean restaurants in that area, operated by the North Korean government. Those restaurants often sold North Korean films on the side. I bought every film available. Later, I got in contact with researchers specializing in North Korean cinema at universities in South Korea and Japan. We frequently helped each other out with film copies. That way, it was possible to see almost any North Korean film I was interested in. |  Order No. 027 (1986) |

- We know that you used to organise special North Korean film series screenings in Europe. Could you provide more information about these endeavours? How did Western audiences react to DPRK movies?

That was my film tour in Spring 2000. I got a package of nine North Korean feature films from the Korea Film Import & Export Corporation. Most of the films had no subtitles, so I used a digital subtitling machine that displayed the subtitles below the actual images. I had to operate that subtitle machine by myself. Therefore, I had to travel to all the screenings, transporting the film prints and that large digital display contraption in a rental car.

The premiere was at the Gothenburg Film Festival in Sweden in January 2000. Gothenburg was very interesting. The martial arts movies were sold out and celebrated by the usual martial arts crowd, showing up in their heavy-metal T-Shirts and so on. The more political films were heavily debated after the screenings – by a very small crowd of concerned university professors and other intellectuals.

My favorite city for the shows was Berlin. There, the press was very sarcastic about the shows with headlines like: “The most decadent thing to do tonight: Watch a North Korean hero epic while the country starves to death.” Drastic humor for sure but not that far away from my own point of view.

|

I think, Hong Kil Dong might be the easiest movie to start with. Easily available on YouTube and a very enjoyable movie. From there, YouTube points you to other movies... so you get to the political ones and so on. This suggests that the movie is dear to most North Koreans - even to the ones who decided to leave. |

- What are your thoughts on the potential future of North Korean cinema?

There are many Western movie makers eager to shoot films in North Korea. Comrade Kim Goes Flying (2012) comes to mind. I would expect a lot more of those international collaborations.

- Thank you for the interview.

If you are interested in reading current articles by Mr Schönherr, please refer to JapanVisitor. The interviewers also recommend the following materials if you can't get enough of information about the the only, true, socialist movie paradise: The North Korean Films of Shing Sang Ok * North Korea Handbook * Kim Jong Il & Hollywood: A Tale of Kidnapping, Videotapes and Sean Connery * The Lovers and the Despot (documentary) * North Korean Film Madness (documentary) * North Korea: Mass Games Performance 2018 * Kim Jong Il: On the Art of Cinema * A Kim Jong Il Production: The Extraordinary True Story of a Kidnapped Filmmaker, His Star Actress, and a Young Dictator's Rise to Power (by Paul Fisher) * North Korea Bans Formerly Approved Films Now Deemed Sensitive * Tatiana Gabroussenko's editorials about NK movies and dramas * North Korea's Cinema of Dreams (documentary) * Korean Film Art (by the Korea Film Export & Import Corporation)