"It's ridiculous!"

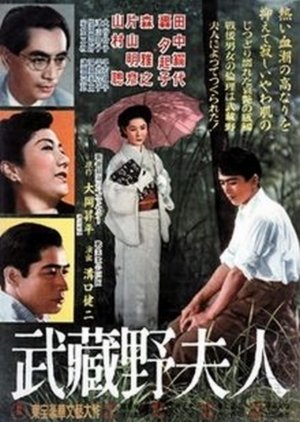

Director Mizoguchi Kenji threw me for a loop with The Lady of Musashino. Unhappy marriages, infidelity, and premarital sex abounded in this postwar film. The main couple exemplified the changing lifestyles and social norms being explored as Japan tried to find its footing after everything came tumbling down. Michiko was as traditional in her morals as her husband was laissez faire regarding his.After fleeing Tokyo during the bombing, Michiko and Tadao go to live with her parents. Her family comes from a long line of samurai and the property has been in the family for ages. After her parents die, Michiko inherits it. Three years after the war, her cousin Tsutomu finally arrives home after having spent time in a Singapore POW camp. Tadao is a professor who believes that infidelity is an expression of free will and proceeds to live out that philosophy. He encourages Tsutomu to live in town while attending university so that he can enjoy as much sex as possible. Michiko’s cousin Ono and his wife Tomiko have their own open ideas about marriage fidelity as well. Both Michiko and Tsutomu have a love for Musashino which develops into feelings for each other. Will Michiko’s rigid morality stay in place in the face of handsome Tsutomu’s advances?

Mizoguchi at first seemed to be conveying the idea that women were treated unfairly in marriage and divorce. Tadao was thoroughly reprehensible even as he lauded the new law being passed that would no longer make it a crime for women to commit adultery, men could continue to do whatever they wanted as always. It was difficult to be invested in this story as most of the characters were selfish and unlikeable. Even Michiko’s noble idiocy began to wear thin. Tadao made a mockery of their marriage and her and even tried to leave her homeless yet she still made excuses for him. While it was true that women could become boxed into a corner with few exits, Michiko could only see one due to her narrow views. Like me, love-stricken Tsutomu had trouble understanding her train of thought. When she tried to explain why they couldn’t be together at the moment, “If there are more and more unhappy people, morality will change,” it wasn’t long before Tsutomu replied, “It’s ridiculous!” The moral of the story was pretty convoluted by the end.

What was effective in this film was the camera work. This was a magnificent film to look at even in black and white. Tsumoto’s arrival through the trees and fog was stunning. I would love for it to have been in color in order to bring out all of the hues of the forest and water as Michiko and Tsutomu explored Musashino on several occasions.

Mizoguchi repeatedly stressed how “everyone is running around in a fever with no morals.” The societal anxiety of a postwar Japan was felt in nearly every scene. The decline of traditions represented by the old samurai estate appeared to not only be caused by Western influences but as a reaction to a way of life that led up to the war and during it. Near the end of the war Michiko was given cyanide for the family by the military when she went out to buy their rations. While she thought about taking it, others around her told her how cowardly and ridiculous it was and the same response was given when a family member died “honorably” by taking his life.

The Lady of Musashino was an uneven melodrama and criticism of changing mores. The memory of the “simple, green, beautiful” Musashino that had helped Tsumotu endure while being a prisoner was fading as quickly as the old way of life. Faithful Michiko arduously clung to the traditions of the past and paid a terrible price for her stubborn morality and sense of duty.

29 April 2024

Considerați utilă această recenzie?